Finger Injuries and Climbing

Do you love to climb, but have finger injuries? Here is some good advice.

What climbers fear most isn’t heights, falls, or mangled toes—it’s finger injuries. And with good reason: While climbing is a full-body exercise, fingers make the most contact with the rock, thus taking more abuse than other limbs, especially from pockets.

Injuries

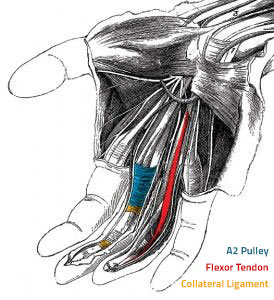

The three finger injuries that climbers frequently experience are an A2 pulley strain or rupture, a flexor tendon tear, or a collateral ligament strain.

A2 Pulley Injury

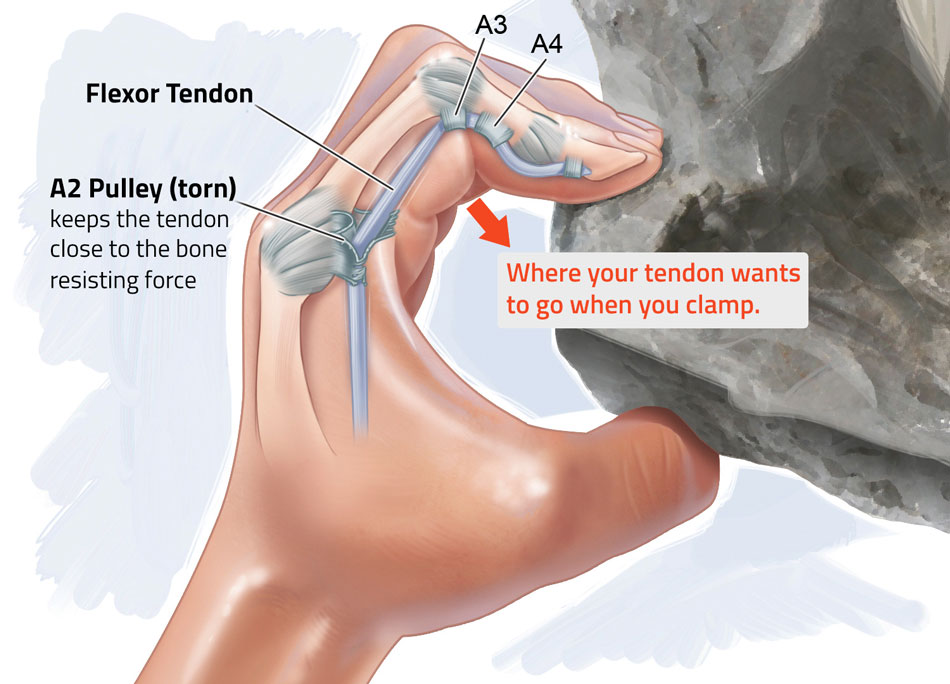

The most common problem is an injury to an A2 pulley—bands of fibers that hold tendons flush to the bone, located in the meaty area between the base of the finger and the middle knuckle. Such injuries often happen when you’re crimping and a foot slips, putting unexpected force on the hand. Climbers may hear an audible “pop” and feel immediate pain, followed by swelling and possibly bruising later. The pain is usually localized to the base of the finger. An A2 pulley injury is the least serious of these three, as it usually doesn’t affect your strength significantly. It’s not recommended to have surgery even with a full rupture. However, you’ll likely always have to tape the finger after a rupture for support.

The most common problem is an injury to an A2 pulley—bands of fibers that hold tendons flush to the bone, located in the meaty area between the base of the finger and the middle knuckle. Such injuries often happen when you’re crimping and a foot slips, putting unexpected force on the hand. Climbers may hear an audible “pop” and feel immediate pain, followed by swelling and possibly bruising later. The pain is usually localized to the base of the finger. An A2 pulley injury is the least serious of these three, as it usually doesn’t affect your strength significantly. It’s not recommended to have surgery even with a full rupture. However, you’ll likely always have to tape the finger after a rupture for support.

Flexor Tendon Tears

These tendons run from the inside of the elbow, down the forearm, and into the fingers, passing beneath the pulleys. They connect muscles and bones, allowing you to bend your hand and flex your fingers. When a tear or stretch occurs, pain is usually felt between the palm and wrist. You might experience an inability to bend one or more joints in a finger, and tenderness or numbness in the finger. If it’s a complete rupture, it likely will not heal without surgery.

Collateral Ligament Strains

The third injury occurs in the collateral ligaments, which surround each finger joint. Trauma here usually happens with sideways loading, such as when you’re gastoning or sidepulling with one hand and throwing up and out to a hold with the other. Pain will be felt at the side of the joint—usually the middle joint of the middle finger. This is another injury that might require surgery if severe enough.

The third injury occurs in the collateral ligaments, which surround each finger joint. Trauma here usually happens with sideways loading, such as when you’re gastoning or sidepulling with one hand and throwing up and out to a hold with the other. Pain will be felt at the side of the joint—usually the middle joint of the middle finger. This is another injury that might require surgery if severe enough.

Treatment

First, stop climbing immediately. If you can’t see a doctor right away, physical therapist and climber Aimee Roseborrough recommends assessing your hand for the next several days to determine how severe the injury might be. Meanwhile, she recommends combining ice baths (10 minutes, three to five times a day) with active range-of-motion exercises (gentle stretching and flexing) for the affected finger. The first 72 hours are most critical with icing, and you should continue the ice baths as long as there is pain with movement.

If bruising occurs, or if your joint is unstable and moving more than normal, see a doctor. If no bruising occurs, but there’s no improvement after resting and icing for five to seven days, make an appointment. The doctor might perform an MRI or diagnostic ultrasound to identify the problem, and will then make a treatment plan.

Recovery times vary depending on severity, but four to six weeks is a baseline guide for healing. A graduated approach— easy routes, big holds—is the best way to ease back into climbing once the pain is gone.

BoulderCentre can help. Call us (303) 449-2730 and ask to see one of our certified physical and hand therapists or visit our hand surgeons page.

Article courtesy of Climbing, an online newsletter.